Julkaistu: 4.3.2016

Aihepiiri: Blogi

(Tämä kirjoitus on yhteenveto WEC Finlandin 3.3. järjestämästä keskustelutilaisuudesta. Tilaisuuden puhujat olivat Fingridin toimitusjohtaja Jukka Ruusunen ja Vattenfallin tuotannosta vastaava johtaja Torbjörn Wahlborg. Kirjoitus on tulkintani esityksistä.)

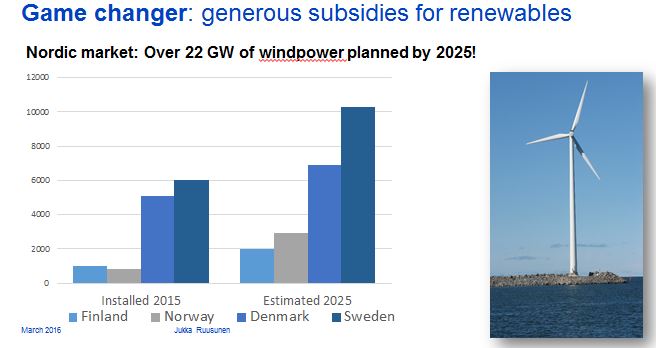

Nordic and European power markets are in a crisis due to the combined effects of continuing recession, low EU emission allowance price and renewable subsidies. Together, they have virtually halved electricity prices (now at historically low levels) in just few years.

The developments over the past years have forced many utilities to prematurely shut down existing (condensing) capacity that is mostly replaced by subsidized wind and solar energy. Ultimately, phasing out fossil powered generation is one clear goal of EU’s energy policy but according to Fingrid’s Ruusunen “we may be going too far fast”. In other words, if too much reliable capacity is phased out too quickly, we will face much higher prices and even blackouts during periods of high demand. Major blackouts would likely shift the focus of energy policy towards security of supply – with the expense of other targets.

Markets are not delivering anymore

European electricity markets were mostly liberalized in the 1990s with the aim of increasing the efficiency of the power system. So far the market participants have shown they can reliably operate and manage (multinational) system stability without a need for centralized operation.

In the Nordic market the rules of the game changed as an unintended consequence of the rapid buildup of huge amounts of wind energy. The impact has been reinforced by the fact that the market was already saturated due to flat demand and abundant supply from existing (nuclear and hydro) plants.

As a result, market based investments have become very scarce and even operating units have hard time making profit. In addition these struggling units can’t be replaced by intermittent sources of energy (i.e. wind) alone. Power is needed irrespective of the whims of mother nature.

How to address the dilemma then?

Focus of energy policy is too narrow

According to Ruusunen, the realization that the crisis is multinational in its nature hasn’t dawned on the decision makers quite yet. Therefore he insisted for increased cross border dialogue and cooperation between all the actors responsible for formulating national energy policies. In addition, Ruusunen explicitly wished that Jorma Ollila would include these thoughts in his report on energy policy in the Nordics that he is compiling for to Nordic Council.

Finally, another challenge for decision makers is the acuteness of the situation. It would require quick and firm action as the Swedish nuclear shut-downs clearly demonstrate.

Vattenfall’s existential worries

Vattenfall’s Torbjörn Wahlborg shared Ruusunen’s account of the overall situation. As evidence of the unfolding crisis, he reminded that one Swedish reactor, Oskarshamn-1, was permanently shut down last year. In addition, Wahlborg highlighted that the rationale for the shutdowns are purely commercial, not political.

However, in the case of Swedish nuclear power, there is a political element involved in the tangle. Swedish nuclear operators pay a special tax that equals roughly 7€/MWh, or a quarter of the operating costs of the plants. The total annual revenue from the tax is roughly 500 M€.

Together, the tax and low wholesale prices of electricity have pushed the existing plants “on the red” (picture above). A situation where market prices are sometimes lower than production costs might be tolerable for a while but the story doesn’t end there. The Swedish nuclear safety authority requires that all nuclear units should install new safety features (independent core cooling systems) as a result of the Fukushima accident. The systems should be installed by the end of 2020.

In order to comply with the regulators demands, the units would require investments totaling up to several hundred million euros and the investment decisions would have to be made within next year.

The scenario of complete nuclear phase-out in Sweden (9650 MW in capacity) by 2021 would of course have major ramifications beyond Sweden. Wahlborg was sympathetic about the such scenario’s potential impacts on the import dependent electricity system of Finland. However, he insisted that Finnish security of supply simply isn’t Vattenfall’s responsibility.

Wahlborg’s call short term solutions included the removal of the nuclear tax. Wahlborg argued that if the tax wasn’t removed its revenue would drop to zero in few years anyway as the reactors would shut down. According to Wahlborg, removal of the tax would also ensure that operational plants and the resources tied to them wouldn’t go to waste.

Similarly to Ruusunen, Wahlborg called for increased and close cooperation between all the bodies responsible for energy policy in the Nordic region.

You can find the presentation slides from both speakers from here.

Lauri Muranen, WEC Finland